Why One-Size-Fits-All Doesn’t Work: The Case for a Biopsychosocial Perspective on Anxiety

Unpacking the Complexities of Anxiety

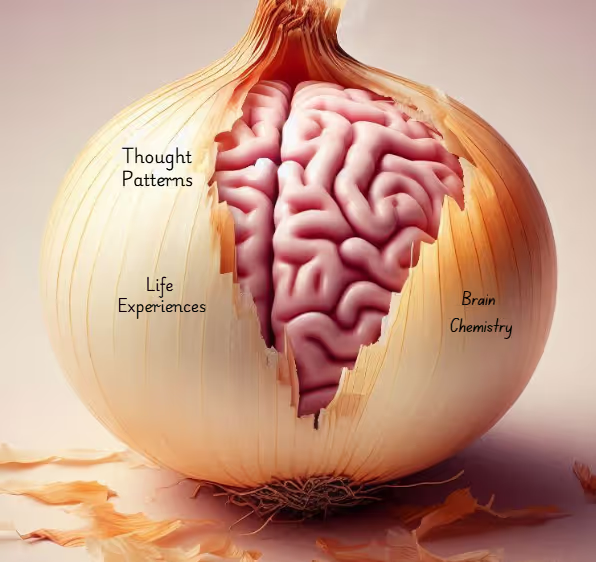

Most people would describe anxiety as feeling nervous, overwhelmed, or worried—sometimes for no clear reason. But anxiety is more than just feeling stressed; it’s a complex experience with many layers, kind of like an onion. What causes anxiety? Why do some people struggle with it more than others? The answers aren’t simple, and that’s part of the problem with how anxiety is often treated.

For a long time, doctors and scientists have looked at anxiety mostly through a biomedical lens—meaning they’ve treated it as a problem in the brain that can be fixed with medication or other biologically-based treatments. While this approach has helped some people, it doesn’t tell the whole story. Anxiety isn’t just about brain chemistry–it’s also shaped by life experiences, thought patterns, and the world around us.

Where the Biomedical Model Is Helpful

The biomedical model has brought some important benefits:

- It validates mental health struggles and gives legitimacy to the distress of those diagnosed, and has arguably reduced stigma and the personal weaknesses falsely attributed to those individuals

- It helps some individuals find relief through medication when other treatments haven’t worked

- It offers a clear, science-based explanation for mental health conditions, which can be comforting to those seeking answers

Where the Biomedical Model Falls Short

The biomedical model, however, oversimplifies anxiety and ignores the bigger picture. Here’s why it has serious limitations:

- Contradictions in Reducing Stigma: The biomedical model is often praised for reducing stigma by legitimizing mental health conditions as medical issues. This perspective does shift blame away from individuals, encouraging them to seek help. Research shows, however, that it does not reduce stigma long-term. Instead, it can lead to a sense of hopelessness by suggesting that mental illness is purely biological and unchangeable, making recovery seem out of reach.

- Too Narrow in Focus: It primarily looks at biological causes while dismissing psychological and social factors that contribute to anxiety, such as trauma, systemic injustices, stress, or rigid thought patterns.

- Low Accuracy in Diagnosing Anxiety: Anxiety can show up differently for everyone, but the biomedical model relies on broad categories that don’t always reflect real-life experiences.

- Doesn’t Always Lead to Better Outcomes: Even though billions have been spent on research and new medications, mental health outcomes as regards anxiety haven’t significantly improved over the years.

- Influence of Pharmaceutical Companies: The promotion of medication as the go-to treatment is partly driven by government policies and pharmaceutical marketing, which dictate what is accessible, while also shaping public perceptions of mental health.

While the biomedical model has played an important role in mental health treatment, it fails to address anxiety as a complex issue that involves the mind, body, and environment. This is why experts are increasingly advocating for a biopsychosocial approach, which takes into account how our thoughts, emotions, and life experiences shape our mental health—offering a more complete and personalized way to manage anxiety.

What Is the Biopsychosocial Model?

The biopsychosocial model addresses anxiety

in three different ways:

Biological Factors 🔬

When it comes to anxiety, it’s not just an experience of the mind—it’s deeply tied to changes in the brain. Research shows that the structure and function of our brains can actually be altered in ways that make us more prone to anxiety. For example, people diagnosed with Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) often have an overactive amygdala—the part of the brain responsible for processing fear (Martin et al., 2009). This means their brains are constantly on high alert, making them more sensitive to potential threats in everyday situations. Meanwhile, the prefrontal cortex—the area that helps us regulate fear—struggles to keep anxiety under control, leading to constant worry and emotional overload.

But it’s not just about brain structure. Neurotransmitters—those chemical messengers in our brain—also play a significant role in anxiety. For instance, low levels of GABA, a neurotransmitter that calms the brain, can send the emotional centres of the brain into overdrive. This can leave you feeling more anxious and overwhelmed. The HPA axis, which controls our stress response, is another key player. When it’s out of balance, the body produces too much cortisol (the stress hormone), which can worsen anxiety.

And of course, genetics come into play. Anxiety often runs in families, suggesting that both our genes and our environment contribute to its development. Consider, for example, someone who struggles with anxiety as an adult, whose parent’s anxiety went unmentioned and untreated due to the era and culture in which they lived. Perhaps their brain at birth was already primed for anxiety, but we can easily imagine that the parenting they experienced as children impacts their current ways of processing events, Disruptions in how the brain regulates fear, paired with genetic predisposition, can increase the chances of developing an anxiety disorder. So, if you’ve ever wondered why anxiety seems to "run in the family," it’s because our brains—and our genetic makeup—play a big part in it.

Psychological Factors 🧠

Anxiety isn’t just about worrying—it’s deeply rooted in the way we think and feel about ourselves and the world around us. Let’s dive into some of the psychological factors that contribute to anxiety and how they might show up in our lives.

One major player is rumination—when we can’t stop thinking about potential threats or replaying past mistakes. This constant overthinking keeps anxiety levels high and makes it harder to move forward, creating a cycle that’s tough to break (Kinderman et al., 2015).

Our relationships also play a big role. Feeling dissatisfied with or threatened by the people around us—partners, friends, coworkers—can significantly elevate the risk of developing anxiety. For many women, discontent with social connections can be a major factor. Women tend to maintain larger, more emotionally intensive social networks, which means they invest more time and energy into nurturing these relationships. While this often provides emotional support, it can also make women more vulnerable to stress when these connections are strained or lack support. Additionally, women are more likely to take on caregiving roles within their social circles, which can lead to emotional exhaustion and a heightened sensitivity to relationship conflict. And let’s not forget about loneliness. It’s a psychological challenge that affects both men and women, amplifying anxiety when we feel isolated.

The quality of our lives matters too. If we’re unhappy or feel disconnected from something meaningful, our risk for anxiety increases. People who struggle with their self-image or feel unsatisfied with their life circumstances are more vulnerable to anxiety disorders (Flensborg-Madsen et al., 2012).

In addition, certain personality traits can make us more prone to anxiety. For example, those who have a high level of temperamental frustration may find it harder to cope with stress, leading to heightened anxiety in challenging situations. Shyness, especially in social settings, can also lead to social anxiety disorder over time, making everyday interactions feel overwhelming. And if someone struggles with low attentional control—meaning they find it hard to focus or regulate their emotions—they may experience amplified anxiety when faced with stress (Narmandakh et al., 2021).

Understanding these psychological factors helps us realize that anxiety isn’t just “in our heads” but is shaped by how we respond to the world and our inner experiences.

Social Factors 🌍

Anxiety isn’t only an individual reality—it’s also heavily influenced by our social environment and the societal pressures we face. One key social factor is gender. Research shows that women are more likely to experience anxiety disorders than men, which can often be traced back to societal expectations. Women are generally encouraged to express emotions, including feelings of anxiety, whereas men are often expected to appear strong and independent. This societal pressure to suppress emotions may contribute to why anxiety is more commonly diagnosed in women, with gender roles playing a major part in how anxiety is both experienced and expressed (Narmandakh et al., 2021).

Socioeconomic status (SES) is another important dimension influencing anxiety. People from lower SES backgrounds are at a higher risk of developing anxiety disorders, especially girls. The stress that comes with financial instability, limited access to resources, and fewer opportunities for personal or social growth can all contribute to heightened anxiety. (Narmandakh et al., 2021). Meanwhile, high quality nutrition and the type of sleep that can be consistently enjoyed in safe, quiet, climate-controlled housing impact brain development.

Parental mental health can also significantly affect the development of anxiety in individuals. When parents struggle with depression or anxiety, they may find it challenging to provide the emotional support and guidance their children need. This lack of support can leave people more vulnerable to developing anxiety themselves. For those who grew up with parents facing mental health challenges, forming healthy social relationships may become difficult, which can heighten feelings of isolation and worry (Narmandakh et al., 2021).

Experiences of childhood adversity—such as the loss of a parent, parental divorce, or abuse—also contribute to greater risk for developing anxiety. Early traumatic experiences can have lasting effects, often fostering unsustainable coping strategies for stress and anxiety.

Why the Biopsychosocial Model is the Better Approach for Anxiety

When it comes to understanding and treating anxiety, the biopsychosocial (BPS) model offers a more complete picture than the traditional biomedical model. The biomedical approach focuses mostly on things like brain chemistry and genetics. While advances in this area, such as neuroimaging and studies of neurochemicals have been impressive, there’s still no clear “anxiety gene” or definitive biomarker that can pinpoint the problem. Despite these advances, patient outcomes haven’t improved drastically (Tripathi et al., 2019).

The BPS model, on the other hand, looks at the whole person. It recognizes that anxiety doesn’t just come from your biology—it’s also shaped by your thoughts, feelings, and the world around you. This model considers how your unique genetic makeup, your mental health, and your social environment all come together to influence your experience of anxiety. It’s not just about what’s happening inside your body, but also about how life’s stressors, relationships, and past experiences play a role.

One of the coolest things about recent research in genetics (called epigenetics) is that it shows how your environment can actually influence your genes. This means that anxiety isn’t just something that’s “written in your DNA” — your surroundings and life events matter too.

The BPS model produces personalized care. Everyone’s experience of anxiety is different, so why should everyone get the same treatment? Instead of taking a one-size-fits-all approach, the BPS model takes into account your biology, your thought patterns, and your life circumstances to create a treatment plan that works for you. This might mean a mix of talk therapy, medication, walks in the forest, and support from friends or family to tackle anxiety from multiple angles.

By combining biological treatments with psychological support and social interventions, the BPS model doesn’t just help ease anxiety in the short term—it also supports long-term well-being, giving individuals the tools to manage their anxiety more effectively.

A Holistic Approach to Anxiety: How the Biopsychosocial Model Shapes Treatment

Anxiety isn’t just a mental struggle—it affects the body, mind, and our relationships to others and to the world. That’s why the biopsychosocial model (BPS) is such a game-changer when it comes to treatment. It recognizes that biological, psychological, and social factors all play a role, meaning that the most effective treatment plans combine different approaches, creating a well-rounded strategy for managing anxiety.

So, what does that look like in practice? Let’s break it down.

Psychotherapy:

- Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT): CBT is a well-researched treatment for anxiety disorders, helping individuals identify and reframe negative thought patterns and behaviours (Hofmann et al., 2012).

- Exposure Therapy: Exposure therapy carefully and progressively exposes individuals to things they fear, helping them manage their anxiety in a safe and structured way (American Psychological Association, 2017)

- Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR): EMDR therapy is a structured, step-by-step method for treating trauma and related symptoms. It helps individuals safely reconnect with the memories, thoughts, emotions, and physical sensations linked to the trauma, enabling the brain's natural healing process to work towards a positive resolution.

Pharmacotherapy:

- Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs): Medications like Prozac, Zoloft, and Lexapro help balance serotonin levels in the brain and are commonly used to treat anxiety and panic disorders. Research shows that SSRIs are effective in managing anxiety symptoms.

- Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs): Medications like Effexor and Cymbalta are often prescribed if SSRIs don’t help. SNRIs help raise the levels of both serotonin and norepinephrine in the brain, which can improve mood and reduce anxiety.

Lifestyle and Integrative Interventions

- Exercise: Regular physical activity has been shown to reduce cortisol (the stress hormone) and increase endorphin levels, improving overall mood and resilience.

- Mindfulness and Meditation: Techniques like Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) help regulate emotional responses by promoting awareness of thoughts and feelings.

- Yoga Therapy: Yoga can lower physiological markers of anxiety, such as heart rate and blood pressure, making it a valuable complement to traditional therapy.

- Nutrition and Sleep: A well-balanced diet and healthy sleep patterns play a crucial role in stabilizing mood and supporting brain function.

Social and Environmental Interventions

- Family and Group Therapy: Anxiety is often influenced by interpersonal relationships, making family therapy and support groups beneficial for emotional regulation and social connection

- Nature Therapy: Exposure to natural environments helps lower stress levels and supports nervous system regulation, making activities like walking outdoors or spending time in green spaces helpful for promoting relaxation and emotional balance.

Integrated and Collaborative Care

A truly biopsychosocial approach requires collaboration among mental health professionals, medical doctors, and social support systems. When psychiatrists, therapists, primary care physicians, and community resources work together, individuals benefit from personalized and multidimensional care that fosters lasting improvement.

By integrating these therapies and interventions, the BPS model offers a comprehensive framework for understanding and treating anxiety, addressing the complex interplay of biological, psychological, and social factors.

Conclusion

When it comes to treating anxiety, one size definitely doesn’t fit all. The biopsychosocial (BPS) model takes a holistic view, addressing not just the biological aspects, but also the psychological and social factors that contribute to anxiety. By incorporating therapies like CBT, exposure therapy, and ACT, along with medications like SSRIs and SNRIs, the BPS model provides a much more personalized and comprehensive treatment plan. Add to that lifestyle changes like exercise, good sleep habits, and social support through family or group therapy, and you have a well-rounded approach that can truly make a difference. Anxiety isn’t just about the brain—it’s about how our thoughts, relationships, and daily habits all play a role. That’s why the BPS model is so effective: it looks at the whole person, not just the symptoms, and tailors treatment to fit the individual.

References

- Engel, G. L. (1977). The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science, 196(4286), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.847460

- Foundational article introducing the biopsychosocial model.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Source for diagnostic criteria and biomedical framing of anxiety.

- Hofmann, S. G., Asnaani, A., Vonk, I. J., Sawyer, A. T., & Fang, A. (2012). The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 36(5), 427–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-012-9476-1

- Evidence for CBT as a psychological intervention.

- Shapiro, F. (2018). Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy: Basic principles, protocols, and procedures (3rd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

- Source for EMDR as a trauma-informed treatment.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). (2020). Generalised anxiety disorder and panic disorder in adults: Management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg113

- Guidelines for pharmacological and psychological treatment of anxiety.

- World Health Organization. (2022). Mental health and COVID-19: Early evidence of the pandemic’s impact. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240061321

- Context for increased anxiety and social factors post-pandemic.

- Padesky, C. A., & Mooney, K. A. (2012). Strengths-based cognitive-behavioral therapy: A four-step model to build resilience. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 19(4), 283–290. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1795

- Strengths-based CBT approach mentioned in the conclusion.

- Jo, H., Song, C., & Miyazaki, Y. (2019). Physiological Benefits of Viewing Nature: A Systematic Review of Indoor Experiments. International journal of environmental research and public health, 16(23), 4739. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16234739