Trust the Research, But Trust the Client More: Rethinking Psychotherapy’s Evidence Bias

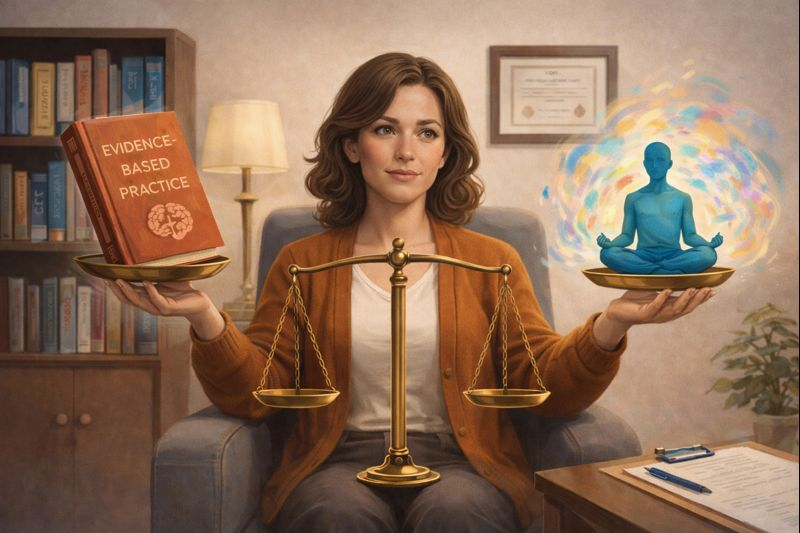

The Psychotherapist’s Dilemma

In recent years, evidence-based approaches have taken the spotlight in psychotherapy, and for good reason: they are consistently described by researchers as the safest, most reliable, flexible, and cost-effective interventions to date. To illustrate, cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) is among the most popular evidence-based practices. A recent meta-analysis of 409 clinical trials on CBT for depression found the intervention to have a moderate-to-large effect size (g = .79), meaning that 79% of depressed clients following CBT had better outcomes than those in control groups, who did not (Cuijpers et al., 2023). With cases like these, the use of evidence-based therapies may appear straightforward, not only because of their efficacy but also their provision of the sweet, scientific validation that the field of psychology has often struggled to achieve.

To hell with older, less scientific, psychoanalytic approaches, I once thought. In my undergraduate psychology courses, these were often presented as fascinating but ultimately too convoluted to be considered “scientific.” They were messy, subjective, and lacked the empirical rigour which we find in evidence-based practices. Yet, many psychotherapists continue to use them (and their variants) in practice (Cook et al., 2017). The divide between evidence-based research, which mainly favours cognitive-behavioural approaches, and practice, which often blends in existential, interpersonal, or psychodynamic methods, has often perplexed me.

This divide highlights the dilemma at the heart of psychological science: individual human behaviour does not lend itself neatly to scientific measurement. What might work for the “average” person in randomized controlled trials studies may not apply to individual persons, sitting across from their therapists. This is where less evidence-based approaches may come into play. Carl Jung identified this problem almost a century ago in The Undiscovered Self:

“Judged scientifically, the individual is nothing but a unit which repeats itself ad infinitum and could just as well be designated with a letter of the alphabet. For understanding, on the other hand, it is just the unique individual human being who, when stripped of all those conformities and regularities so dear to the heart of the scientist, is the supreme and only real object of investigation.” Jung, 1958, p. 6

In other words, individual persons cannot be adequately understood or generalized as per the scientific method, since each individual, in and of themself, is an exception to the norm. For the psychotherapist, this presents another dilemma, which Jung goes on to describe:

“On the one hand, he [the psychotherapist] is equipped with the statistical truths of his scientific training, and on the other, he is faced with the task of treating a sick person who, especially in the case of psychic suffering, requires individual understanding.” Jung, 1958, p. 6

Psychotherapists must understand that individual clients require individualized approaches. Evidence-based approaches are powerful and often effective, but no single treatment fits every case. Individual cases may require the psychotherapist to betray theoretical purity and integrate methods to adequately meet the needs of the individual in front of them.

Regrettably, I have not seen much reflection on this tension. Students learn about the effectiveness of evidence-based practices, but they are not asked to understand why they are inherently better at treating individual persons, which was the focus of older, more holistic approaches. Of course, there is still the option to practice psychodynamic or humanistic therapies, but these are not as “à la mode” as cognitive-behavioural approaches. The former are time-intensive, costly, and harder to measure in randomized trials. By contrast, standardized protocols like CBT offer efficiency, structure, and a reassuring sense of scientific legitimacy.

For instance, CBT’s key principle is easy to operationalize: maladaptive thoughts and beliefs cause psychopathology and mental distress, and, with a proper amount of cognitive restructuring, clients can think of problems more rationally. In other words, the success of this approach depends on the extent to which the client can learn to “think different thoughts.” Nonetheless, this method may overlook clients’ inner complexities by failing to address the unique etiologies of their distress. Engaging in Socratic dialogue with one’s therapist may be statistically effective at making the “average” person think more rationally, but utterly useless to an individual client struggling with deeply-rooted inner turmoil.

Even the science itself is more fragile than it appears. The criteria for what counts as “evidence-based” are debated, and many studies rely on control conditions that bear little resemblance to real-world practice (Cook et al., 2017). Mechanisms of change remain murky, and what looks statistically significant may not always be clinically meaningful.

Psychotherapists, then, must apply evidence-based approaches with some degree of discretion. Evidence-based methods provide a solid framework for practice. Still, clients have distinct histories, contradictions, and needs. The therapeutic relationship, which is paramount to meaningful healing, will also flourish if the client’s strengths and creativity are incorporated and their personal preferences are fully understood by their therapist. The challenge for psychotherapists, then, is to balance scientific integrity and the individuality of their clients while remaining open to insights from other traditions when evidence-based approaches fall short. In practice, this means trusting the research but trusting the client even more.

References

Jung, C. G. (1958). The undiscovered self. Little, Brown.

Cook, S. C., Schwartz, A. C., & Kaslow, N. J. (2017). Evidence-Based Psychotherapy: Advantages and Challenges.

Neurotherapeutics: The journal of the American Society for Experimental NeuroTherapeutics, 14(3), 537–545. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-017-0549-4

Cuijpers, P., Miguel, C., Harrer, M., Plessen, C. Y., Ciharova, M., Ebert, D., & Karyotaki, E. (2023). Cognitive behavior therapy vs.

control conditions, other psychotherapies, pharmacotherapies and combined treatment for depression: a comprehensive

meta-analysis including 409 trials with 52,702 patients. World psychiatry: Official journal of the World Psychiatric Association

(WPA), 22(1), 105–115. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.21069