Attachment Styles Unmasked: Your Nervous System’s Dating Script

Attachment Styles in Adult Relationships

We hear the term “attachment style” a lot when talking about relationships. Maybe you’ve even taken a test to know what yours is. I know I have! However, I think the word “style” can be a bit misleading. It kind of sounds like something you choose or prefer, when in reality your attachment patterns began as survival strategies of the nervous systems. So what is an attachment style and what does it mean for our romantic relationships?

Let’s explore where attachment theory comes from and how it affects the way we handle conflict to how comfortable we feel being vulnerable.

What Does Attachment Style Actually Mean?

Attachment theory was first developed by Mary Ainsworth and John Bowlby, to describe how infants formed relationships with their primary caregivers. The theory further explains why we form and maintain relationships the way we do.

John Bowlby believed that children’s early relationships with their caregivers is linked with how they may connect with others throughout life. Psychologist Mary Ainsworth furthered this idea by running her Strange Situation studies, establishing three attachment styles in infants: secure, anxious, and avoidant.

- Secure attachment in children

Secure attachment is formed when a caregiver is consistently responsive to their child’s needs. These children feel secure forming close relationships with others. They do not worry about being overly dependent on others nor do they fear being abandoned.

- Anxious attachment in children

This attachment style arises when a caregiver is inconsistent - they are sometimes there, sometimes not. This leaves children desperately wanting a close relationship, but feeling unworthy of one. They become distrustful and fearful of abandonment. Once in close relationships, they may be jealous and possessive.

- Avoidant Attachment in Children

Avoidant attachment style is a result of caregivers frequently dismissing their child’s needs or being emotionally unavailable. These children are less interested in forming close relationships. Once they are in a close relationship, they tend to be less invested in them.

Crisis of Attachment

Humans are wired for connection - it’s how we survive. In current dominant culture, we are seeing what we call a “crisis of attachment,” where caregivers are increasingly distracted. Caregivers are spending more time absorbed in their phones rather than interacting with their baby. Children in grocery carts are kept calm with tablets instead of interacting with the world around them, missing important learning opportunities. These small disconnections might not seem disastrous but the accumulation of them can be detrimental for how a child learns to relate, communicate, and feel safe with others in the future.

What can this look like in adult relational-conflict?

Attachment styles don’t stop at childhood. Attachment patterns as a child are relatively stable throughout life. When we form close relationships with romantic partners we may find these same patterns. Have you ever noticed that in relational-conflict some people remain calm while others spiral or shut down.

Secure Attachment

People with secure attachments when discussing conflict with a romantic partner are less likely to be angry. They attribute less hurtful intent to their partner’s actions. They focus on more positive outcomes of conflict and are more likely to be forgiving. For example, they might think: “We’re just having a disagreement, not a disaster.”

Anxious Attachment

Those with anxious attachment perceive conflict as more frequent and severe with their partners. This results in the person feeling more hurt. They may perceive a negative future for the relationship. They might take a delayed text response from their boyfriend as losing interest.

Avoidant Attachment

During conflict, people with avoidant attachment tend to distance themselves emotionally from the conflict altogether. Instead of staying in conflict, they may withdraw from conflict resolution. For example, they may avoid the situation entirely or not speak in conversation. Consequently, the conflict remains unresolved or results in an escalated problem.

Expanding the Model - Kim Bartholomew

Kim Bartholomew expanded on Ainsworth and Bowlby’s attachment theory with a new model. This two-dimensional model conceptualizes the self and the others. Representation of the self is either positive or negative and the representation of the other is also either positive or negative.

The positive self-dimension involves an individual being self confident rather than anxious in close relationships. The positivity of the other dimension involves seeking out others for support rather than avoiding closeness.

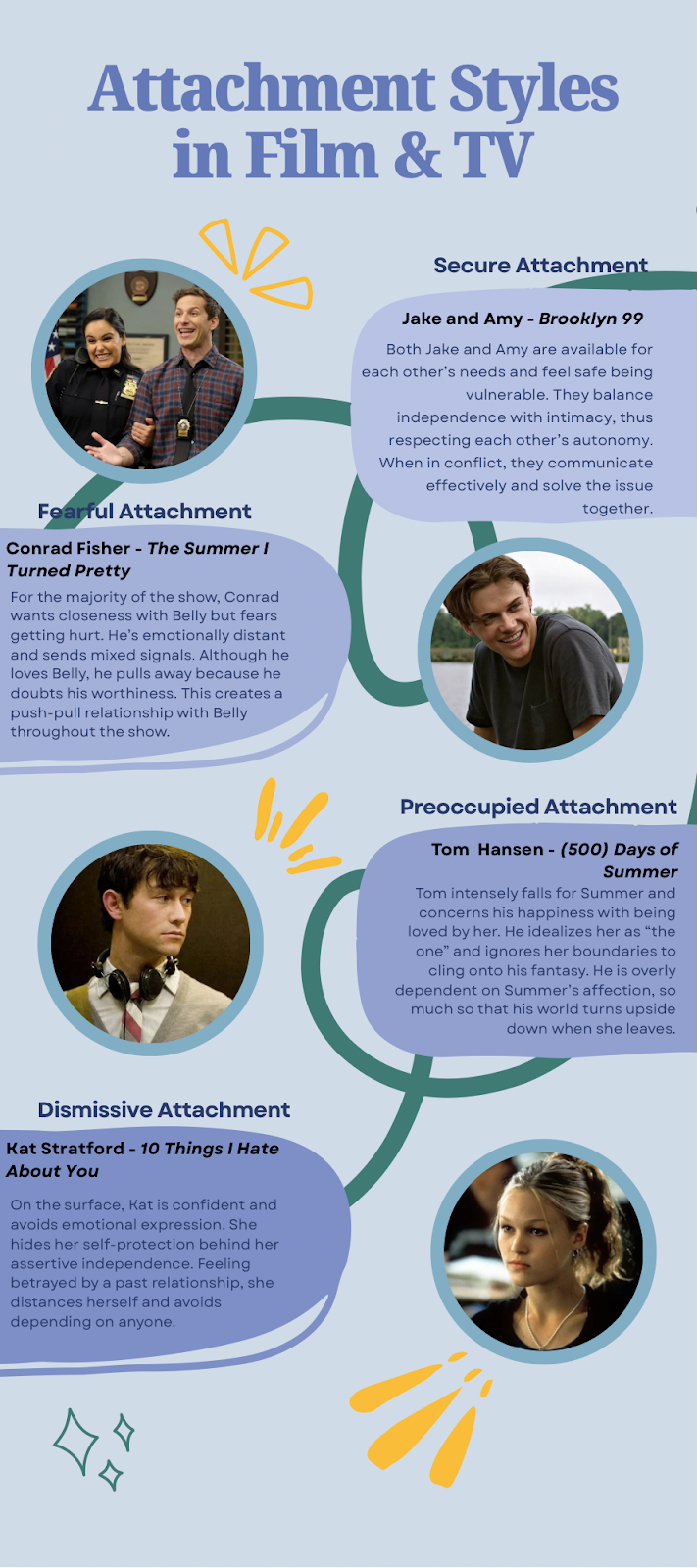

Secure Attachment - Positive View of Self and Others

This attachment style involves having a high self-esteem and self-confidence. Those with this attachment are comfortable with intimacy in relationships while maintaining autonomy.

Fearful Attachment - Negative View of Self and Others

This is the most problematic attachment as it is negative on both dimensions. This entails a low self esteem and high attachment anxiety. Those with fearful attachment desire relationships but avoid intimacy because they fear getting rejected.

Preoccupied Attachment - Negative View of Self, Positive View of Others

This attachment style involves having a low self-worth. Consequently, those with this attachment excessively depend on others to give them a sense of love and approval. They are overly invested in relationships and may be perceived as needy or demanding.

Dismissive Attachment - Positive View of Self, Negative View of Others

This attachment is characterized by being self-reliant in close relationships. Due to a negative view of others, those with this attachment are distant in relationships. They may minimize the importance of intimacy.

Now we know a bit about attachment styles, the secure and the not-so secure. What can we do when we see ourselves in the not-so secure attachments?

Moving from an insecure attachment to secure

Attachment styles aren’t definite. Although the way we connect is shaped by early experiences, we have the capacity to change. By putting the work into ourselves, we can shift from an insecure attachment to a secure one.

Awareness of your attachment patterns

It’s important to know what kind of style you have. Understanding your patterns helps identify what needs to be worked on. If you don’t know your style, we invite you to take this quiz:

https://www.attachmentproject.com/attachment-style-quiz/?utm_source=

Emotional Regulation

Having an insecure attachment affects how you respond to certain emotions. Learning how to self-regulate is crucial for responding to triggers and overcoming anxious attachment. Using mindfulness during conflict, and being aware of your surroundings helps you work collaboratively in your relationship to solve the problem.

Self-regulation can be:

- Learning how to come down when emotions are heightened

- Avoiding emotional outbursts when overwhelmed

- Handling conflict without aggression or hostility

Building Self-Esteem

Those with insecure attachment often worry about being abandoned, being rejected, not being worthy, and more. Building self-esteem will help you have less of these worries and have less of a need for constant reassurance. Growing to understand that other’s actions are not a reflection of your own worth is helpful for changing thought patterns and insecure attachment.

Therapy

Therapy is a great resource for introspection and goal setting. Therapy can help you:

- Identify insecure attachment patterns

- Explore how your attachment style affects your relationships

- Discover ways to create secure and healthy bonds with others

Attachment styles are relatively stable through life, but are not fixed. If you’re interested in exploring your attachment style and relationships, we’d love to help. Book a free 15 minute chat with one of our psychotherapists today (insert link). Let’s take the first step together in moving towards greater security.

Citations

- Bretaña, Alonso-Arbiol, Recio & Molero (2022), Avoidant Attachment, Withdrawal-Aggression Conflict Pattern, and Relationship Satisfaction

- Bahou, C. (2023, September 26). How to fix an anxious attachment style.

- Medical News Today. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/how-to-fix-anxious-attachment-style?utm_source

- Griffin, D. W., & Bartholomew, K. (1994). Models of the self and other: Fundamental dimensions underlying measures of adult attachment.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology: Interpersonal Relations and Group Processes, 67(3), 430-445. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.3.430

- McLeod, A. (2025, April 20). John Bowlby’s attachment theory. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/bowlby.html

.jpeg)